When is it OK to say ‘no’ in the workplace?

- 17 December 2021

66% of UK employees want to improve their work-life balance - and are looking for managers to help them do this. MaryLou Costa delves into the psychological struggles behind saying no at work and what marketing leaders need to be aware of.

Marketing director Tracey Wallace has learned a valuable lesson this year about what it means when team members push back on work tasks.

Her team at MarketerHire, an on-demand marketing talent platform, stood their ground when it came to issuing their newsletter twice a week. Against Wallace’s instructions to run the test for a full quarter, her editor-in-chief recommended calling time on it after a month. Open rates were down, and splitting the original newsletter in two, which was the intention, ended up creating the workload of two full newsletters.

“The team was getting overwhelmed with the extra work, and we weren't seeing returns after a month of running the test. I wanted to give it a bit more time, but our editor-in-chief very kindly said, ‘no’, presented the 'why', then we stopped and went back to only once per week,” Wallace recalls.

“The newsletter is long again, but the team is far happier - and open rates are back up.”

The experience prompted Wallace to come to the realisation that when team members muster the courage to say no, it’s a sign for a manager to dig in and listen.

“ When team members muster the courage to say no, it’s a sign for a manager to dig in and listen.”

- Tracy Wallace, marketing director, MarketerHire

“Is this a bandwidth issue? Is there something about the strategy they don’t agree with? Does this fall under their responsibilities and does everyone agree that’s the case? Why someone is saying no is just as important as their ability to do so. By digging in, you get a better sense of what the team is working on, where the bottlenecks are, and how to solve those problems in the future,” says Wallace.

“None of us are machines. We all need to recharge. We all need to disconnect. The goal of a business is to work together to get projects over the line, but we don’t all have to be working at the exact same time, or on the exact same thing, to make that happen. Open communication can be hard to cultivate, but it’s required in the knowledge worker economy to reduce stress, maintain autonomy, and help folks achieve their career goals.”

Burnt-out workers are looking to leaders

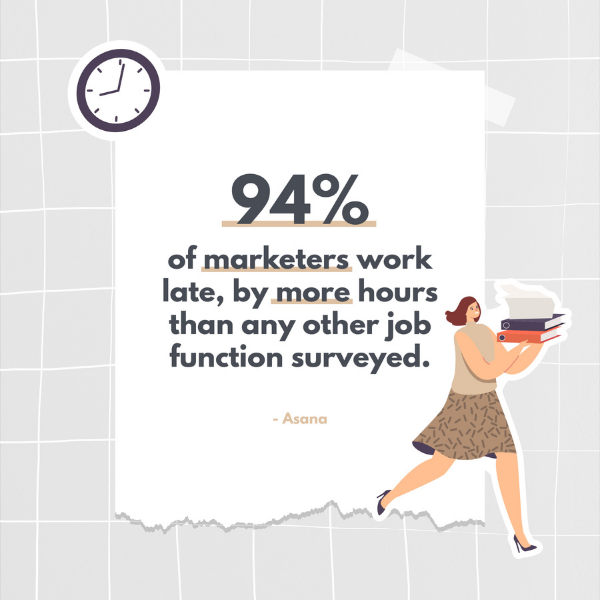

The pushback Wallace dealt with is more likely than ever to be happening in workplaces as stress and burnout become widely felt and acknowledged. A survey of 600 knowledge workers in the US by automation platform Zapier, found that 75% have the responsibility of more than one employee since the pandemic started, with 71% experiencing burnout in the past 18 months.

Marketers in particular are overloaded, according to a global study by the work management platform Asana study. It highlights that 94% of marketers work late, by more hours than any other job function surveyed, because of factors like too many meetings, and spending 62% of their time on ‘work about work’. This leaves marketers just 21% of their time to spend on skilled work and 17% on strategy.

“None of us are machines. We all need to recharge.”

- Tracy Wallace, marketing director, MarketerHire

The solution? Well, further research from jobs platform Glassdoor, which surveyed 2,000 UK employees, found that 66% intend to make changes to improve their current work-life balance and, as Wallace found, are looking for employers to offer a more nuanced solution to help them protect their personal life.

Breaking the cycle

It took communications manager Andrea (not her real name) a change of job to break the seemingly endless cycle of being overloaded, as feedback to her managers went unheeded in a culture she believes was highly toxic.

“Now, I think part of being a good leader is that saying no is just as important as saying yes”

“I think back then, you didn't have the empowerment to say no. The power balance was hugely skewed. You couldn't say no, because if you did, it was catastrophic,” Andrea reflects.

“Now, I think part of being a good leader is that saying no is just as important as saying yes. Because if someone's come to you and suggested something that you think won’t work, or won’t help the business from a commercial perspective, then you have to say no - that is your job.”

The pandemic and remote working have made it more difficult for people to place boundaries around work and home says cognitive behaviour therapist Somia Zaman. The overall struggle to say no comes down to a fear of the negative consequences, she adds, as Andrea hinted at.

“For some, it comes down to an unrealistic perfectionism: being scared to let anyone down or to be seen not to be able to do something. At the most extreme end, people may worry that they might lose their job, miss out on promotion or be ostracised at work if they ever say no to anything that is asked of them,” says Zaman.

“...people may worry that they might lose their job...”

-Somia Zaman, cognitive behavioural therapist

She recommends not suffering in silence: “At the end of each day, consider spending five minutes doing a self-reflection on how your day’s been: what things went right and what didn't. Think about the reasons for that, as well as what you could do to change that in the future.”

Recognising the impact of choices

Margo Manning, author of ‘The Step-Up Mindset for Senior Managers’, says senior executives can fall into the trap of wanting to be seen as a “fixer”, in what she dubs “superhero syndrome”, which is a dangerous path to burnout.

“Your personal and social identity becomes part of this. You will relish the attention bestowed upon you, and you’ll be looking to be more reactive than proactive. The issue with being reactive is that it never allows you time to step back and consider longer-term fixes. For some firefighters, they just don’t want the drama to stop,” Manning explains.

To stop the cycle, those in this situation need to “take off the cape” and know which fires they need to extinguish, recognising that the choices made have a direct impact on wider teams.

Ultimately, communications manager, Andrea notes, if an executive is confident in how hard they work for an organisation and the commitment they bring, they’ve earned the right to say no to requests they’ve assessed as not adding value.

Find out more about building your self-confidence and creating trust and rapport with others in your organisation with our Confidence, Influence and Impact course.

- 0 views

FAQs

FAQs

Log in

Log in

MyCIM

MyCIM